As a consequence of a long-term, low-turnover approach, a portfolio necessarily generates deferred tax liabilities. These are taxes which would be owed on capital gains (net of any taxable capital losses) if every security were liquidated. Securities held for less than one year are taxed as ordinary income, while long-term gains on investments held longer than a year are taxed at a more favorable rate. While seemingly sounding like a negative, such as a mounting debt, deferred tax liabilities can be very, very valuable to an investment program.

Deferred taxes are indeed a real liability. However, because of the way the tax system is structured, the liability is not due until the gain is actually realized via a sale. In other words, the investor can control it. This is one way that “Main Street” investors can turn the system around and achieve better results than Wall Street (it rarely happens, as it turns out, but that’s another story). Because taxes are only triggered by means of a sale, an investor can elect to hold off – or defer – the taxes until a later date. If you buy a good company that you are content to hold onto for a long time, assuming the market has correctly appraised its value above your purchase price, you can decide to ‘let it ride’ for as long as you wish. In many wealthy families investments are held decades or even generations. In these cases an additional benefit is gained through the cost basis ‘step up’ the IRS gives to heirs inheriting the assets.

To illustrate the value of deferred taxes a short parable might be helpful. After all, what’s the difference between paying the tax every year, vs. waiting until the end? Large as it turns out, and only more so over time.

The Parable of Paul and Dexter

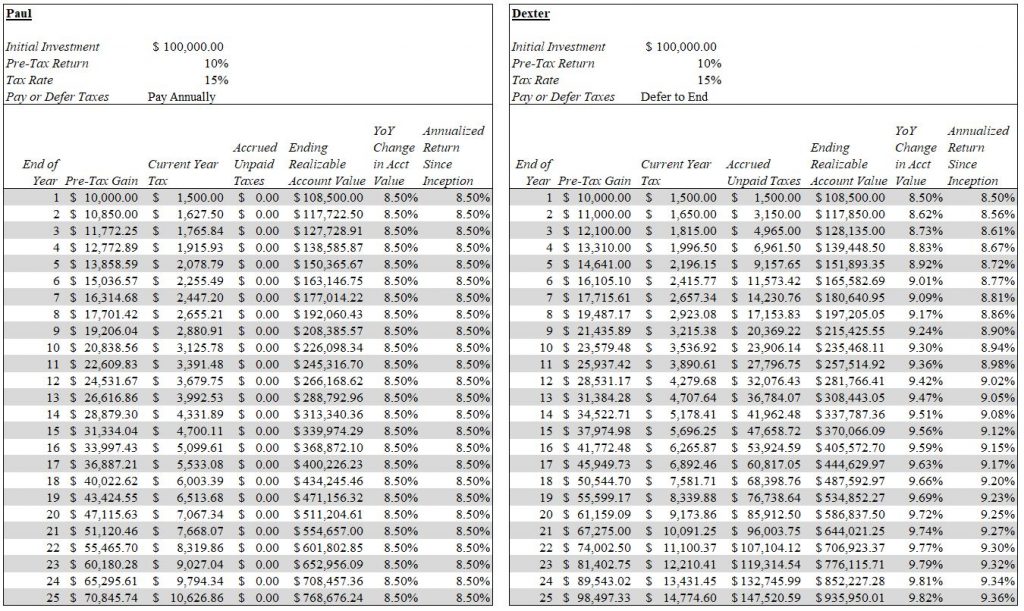

Let’s assume two investor friends find an investment that is guaranteed to return 10% annually, without fail. (We’ll leave aside the obvious misgivings about the prospects of a guaranteed return of any kind.) Also let’s assume that each investor does not need any of the money until after his investment program has completed its turn, and the security doesn’t pay a dividend. Lastly, both are subject to a 15% long-term capital gains tax rate. Both men are busy going about their lives, and leave their broker instructions on how to handle their investment programs. At the beginning of the program each man puts $100,000 to work.

One man, Paul, instructs his broker to sell the investment after each year plus a day (to get the favorable long-term capital gains rate), pay Uncle Sam the capital gains tax, and reinvest the proceeds into the same investment. After all, Paul exclaims, “No one ever went broke taking a profit!” He also enjoys seeing the gain appear on his tax return every year and never fails to point out to his wife the “extra income” he is so smartly earning for their family.

Paul’s friend, Dexter, decides on another course. Dexter instructs his broker to maintain his investment without selling until the end of Year 25 when he and Paul have decided to sell everything and retire to a tropical island with their wives to enjoy themselves. Dexter reckons that it’s just as well that things remain simple, and he only need bother paying one tax at the end. Since his accountant has informed him that this is well within the law, he thinks it easier. Dexter also doesn’t mind that nothing will show up on his tax return since he and his wife have decided to put the investment out of their minds entirely until it will actually be needed.

At the end of Year 5 both men decide to compare brokerage statements. Pay-it-now Paul is pleased to see his account is worth $150,366, representing an annualized gain of 8.5% (10% return less tax at a 15% rate, or 1.5 percentage points). Surprised, Paul sees his account value is $1,528 lower than defer-it Dexter’s. Since the difference is only 1.0% and Paul is happy to have reported increasing gains on his tax return every year to his wife, he shrugs it off as inconsequential. The two men decide to check in again after another five years.

Five years goes by and at the end of Year 10 both men sit down to compare. Neither expects to find anything of interest since both started with the exact same $100,000 sum, invested in the same security, and, in fact, used the same broker. However, Paul is shocked to find that his account is now $9,370 or 4.1% lower than Dexter’s. It appears Dexter’s account compounded at 8.9% every year vs. the unchanged 8.5% that Paul’s account increased in value annually. Intrigued, they call their broker for an explanation. Clearly the difference is because Dexter hasn’t paid his taxes yet, Paul thinks, and once that’s taken out it’ll even the score. After explaining to the two men that their accounts are reported to them net of any taxes due – that is, on a “net realizable basis” – their broker mentions how deferring taxes on an investment can produce a slightly better return over time. Still not entirely clear on why the difference exists, Paul and Dexter hang up. Dexter is unconcerned as he has resolved to all but forget about his investment until after the end of Year 25. Paul concludes that because he and Dexter both made the same investment, the difference must be because the broker miscalculated taxes accrued but not paid, and that in the end they’ll end up with the same result.

Fast forward to the end of Year 25. Both Paul and Dexter call up their broker and instruct him to “sell everything”, as the time has come to set sail into retirement. A week passes and the men meet for breakfast to discuss their plans for the future, before going into the bank to deposit their checks together. As they wait in line at the bank, Paul glances down to the deposit slip in Dexter’s hand and emits an audible gasp that catches the attention of all in the bank. Dexter’s deposit slip reads $935,950, while Paul’s own tally’s to $768,676. Visibly upset, Paul leaves the line and heads straight for the door, determined to find out what has happened. Dexter follows Paul who is by now halfway to their broker’s office the next block away.

Dexter joins Paul in their broker’s office and listens as the broker tries to explain to an incensed Paul that his decision to realize gains every year is what caused the discrepancy. Dexter, although pleased to have an extra $167,274 or 21.8% simply by virtue of waiting to pay taxes is intrigued. “Just how has this come to be? It just doesn’t make sense!” The broker pulls out each man’s file and lays them side by side (see Appendix).

Their broker goes on to explain how deferred taxes work like an interest free loan from the government. “Let’s examine just the first two years, and it will become clear how the mechanics work. At the end of Year 1 you both earned 10% pre-tax. Paul, you decided to sell, pay the $1,500 that was due to the Treasury, and reinvest. Dexter, although you didn’t pay any taxes, because you didn’t sell, you still owed the government $1,500 but you weren’t required to remit it just yet. You can both see that at the end of the first year your ‘net realizable values’ were exactly the same $108,500. Dexter, Paul, you’re still with me right?” asked the broker? “Okay…” Paul said, “Go on.”

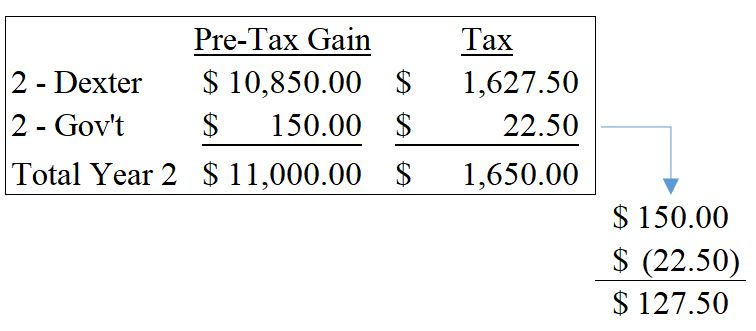

“Let’s break it down a bit, so you can see just how this works.” The broker takes out a piece of paper:

“In Year 2 there was your – Dexter’s – Year 1 realizable account value of $108,500 which earned 10% or $10,850 before taxes. The other $1,500 in your account representing the government’s tax on last year’s earnings also earned 10%, or $150. Now you would think that the whole $150 would be ‘owned’ by the government, right?” The Broker smiled, “But it’s not. Instead, $22.50 is due for taxes on the gain at the same 15% rate as before, but you get to keep the remaining $127.50. The magic lies in the economic reality that deferring income taxes is just like getting an interest free loan from the government; any future gains on that amount, after taxes, are yours to keep. This keeps going on until you sell. You can see that if Dexter hadn’t sold at the end of Year 25 the government’s rightly due cumulative taxes of almost $150,000 would have produced another $15,000. Of course you’d have to pay taxes on that gain so you’d only be left with $12,750, but it’d be real money – over $1,000 per month – that you earned just by waiting. As Warren Buffett has said, ‘Deferred taxes give you the advantage of leverage – having more assets working for you – without the risks’. You pick the due date.” “Wow!” exclaimed Dexter, “That truly is amazing!”

– End Parable –

Ignoring my lack of storytelling ability, the preceding tale illustrates a powerful yet unrealized (pun intended) force in investing. The sad reality is that both Main Street and Wall Street fail to harness its power, despite the latter being deemed “sophisticated” investors.

Among the many reasons for why short term trading exists among professionals and institutions is Pay-it-now Paul’s desire to report gains. The income statements for businesses, like individuals’ tax returns, do not have a line item for unrealized gains. It is only until a gain is realized that it flows through the income statement and into the headlines. Because of short-term thinking, or wanting to impress someone (in Paul’s case his wife; in Wall Streets’ case, investors, boards, the public, etc.), gains are often “harvested” to the detriment of adding real value to an investment program. It would only take a mediocre CEO a few minutes or a paragraph to explain to his or her investors that net unrealized gains belong to them just as much as if they were run through the income statement and that readers of the financial statements should go beyond the reported net income figure. Of course it rarely happens. Many would rather report better results than actually realize them. Their loss, and our gain.

I love your parable on deferred taxes! It is a great example of how the long-term mentality really works for us.

Thank you, @jessierancourt:disqus! My goal here was to show very clearly how the taxes owed to the government remain for your benefit as long as you want them to. It’s that extra reward that comes to long-term investors.